Jerusalem, 15 January, 2026 (TPS-IL) — An Israeli-Japanese breakthrough in quantum particles brings science one step closer to reliable quantum computers. A team of scientists from Israel’s Weizmann Institute and Japan’s National Institute of Materials Science found particles that can “remember” what happened in previous quantum interactions.

The research focused on non-Abelian anyons, exotic quantum particles that appear in ultra-thin materials under extreme conditions and can store information by “remembering” the order in which they move around each other, making them promising building blocks for error-resistant quantum computers.

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature, showed evidence of non-Abelian anyons in bilayer graphene, a material made of two ultra-thin layers of carbon atoms.

“For the first time, we have experimental evidence of particles that behave like non-Abelian anyons,” said Dr. Yuval Ronen, head of the research team. “This research takes us another step toward building quantum computers that are fault-tolerant and more useful beyond narrow research experiments.”

Anyons were first predicted in the 1980s, but only simpler “Abelian anyons” had been observed. Non-Abelian anyons are more complex: they not only change a quantum property called the wave function when swapped, they also change its shape, which encodes memory of previous actions.

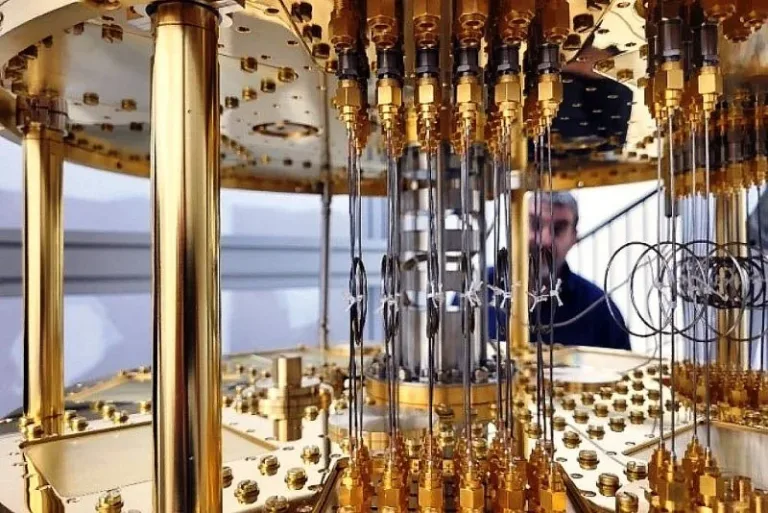

Quantum computers use qubits, which can exist in multiple states at once. This gives them the potential to solve problems that today’s computers cannot. But qubits are very fragile: tiny disturbances can destroy the information they hold. Non-Abelian anyons could solve this problem because they store information across the entire system of particles instead of in a single particle, making them much less sensitive to errors.

“The replacement of non-Abelian anyons leaves a trace in the system’s wave function,” Ronen explained. “If we swap three of these particles in one order, we get a different result than if we swap them in another order. This ability to remember the sequence is exactly what allows them to store information.”

To study the particles, the team guided them along precise loop paths in bilayer graphene and measured the resulting patterns in electrical resistance — a method inspired by a 19th-century light experiment. Surprisingly, the scientists found the particles carried half an electron’s charge instead of the expected quarter, suggesting that two non-Abelian anyons were moving together.

“We haven’t been able to separate them yet, but this is an important step toward observing these particles directly,” Dr. Ronen said. “The next challenge is to see exactly how each order of particle exchanges produces a unique signature. That will bring us closer to fault-tolerant quantum computers.”

According to the researchers, even storing the state of just 300 qubits would require a classical computer to remember more than 34 quintillion numbers, showing just how extraordinary the potential of these particles is for the future of computing.

If fully harnessed, non-Abelian anyons could make quantum computers much more powerful and reliable. They could solve problems that are impossible for classical computers, from predicting chemical reactions for new drugs and materials to improving weather forecasts. They could also strengthen cybersecurity with new types of encryption and advance fundamental science by revealing new quantum behaviors.